From my time at St. Gregory Episcopal in San Francisco…

What does our architecture say about the way we worship and practice corporate liturgy? Saint Gregory of Nyssa Church in San Francisco met in a traditional church when it was founded in 1978 until it built its own church in 1995. Despite being in a traditional setting with pews facing forward, they were able to adapt their liturgy to accommodate singing and dancing and moving about during the liturgy. Being in this setting taught them that they wanted their own space to be adapted to their liturgy and not the other way around. In other words, they made a conscious choice to allow the liturgy to define the space. I suppose this has always been the case with churches, especially older churches that were built during a time period when the priest was the authority and the people sat silently in the pew looking forward. Yet, as liturgy has adapted to local customs, changes in tradition, and lay leader involvement, it seems to be the case that many churches still use the same architectural structure of long spaces with rows of pews facing toward an altar. This may suit the liturgical style of some churches, but my sense is that many congregations could benefit from an architectural structure that is more in tune with liturgical decisions of their community.

I’m not advocating that all churches need to be structured like St. Gregory but I merely use St. Gregory as an example because they have made a conscious decision to fit their space to their liturgy and because this is where I spent my time this summer studying and learning from this community. St. Gregory’s building consists of two adjoining spaces: an octagonal space that flows into a rectangular space. The octagonal space, referred to as the rotunda, holds the altar in the center providing a sort of cradle for the focal point of the church. The beautiful red carved front doors open onto the rotunda where one is greeted by the altar, the focal point of the space. The rectangular space is split in two by the bema and contains chairs on each side of the bema that all face the bema such that people sitting on opposite sides of the bema face each other not the altar. Thus the focus of the liturgy of the word becomes the people and the Holy Scriptures. On one end of the bema is the bishop’s seat where the preacher sits and on the other end of the bema is the table that contains the Holy Book and the incense container.

This rectangular space is based on the ancient synagogue structure, which was modeled after the Jerusalem Temple architecture. The synagogue was traditionally the place where the rabbi, the teacher, taught his students the Torah. In his 1967 book called Liturgy and Architecture, Louis Boyer describes this Temple-inspired structure and its attributes. For St. Gregory, this synagogue-like space configuration allows the participants to give their full attention to each other (facing one another), to the Holy Scriptures (at one end of the bema), and on the preacher and sermon (at the other end of the bema), and is fully the place where teaching and learning happens. At the later service, the choir, which is unaccompanied by instruments other than occasional percussion, is congregated together in the rotunda at the start of the service, but as people move to the rectangular space to sit for liturgy of the word, the choir moves with them and intersperse itself among the participants. I found that this boost of singing among the people encouraged people to sing loudly and use their voices to form a cohesive sung prayer as the entire liturgy is sung.

According to Bouyer, Syrian Churches, discovered through archeological findings, were the most ancient type of Christian churches, and some of this traditional architecture is preserved in the Nestorian churches, Jacobite Syrian Churches and Syrian Catholic Churches. Ancient Syrian churches appear to be Christian versions of synagogues that include:

- Readings and prayers performed on bema, which occupies the center of the nave

- The ark with veil and candle are on one end of the bema

- The seat of the bishop (formerly the seat of Moses) at the opposite end of bema from the ark

- The Christian presiders sit around the seat of the bishop (just as the Jewish elders sat around the rabbi)

- The altar facing east at the end of the space in the apse where the sun rises

(Bouyer, page 25-28)

As the architecture in Christian churches evolved away from synagogues the apse that held the ark became an apse that held the altar, and whereas in synagogues the apse faced Jerusalem, the apse in Christian churches faced east where the sun rose.

As I was walking to Morning Prayer at St. Gregory I noticed that the doors to St. Teresa of Avila, the local Catholic Church, were open so I walked on in to see how their space was configured. Interestingly it was a large rectangular space with the altar in the middle and the pews situated all around it in a giant circle of seating. Unfortunately there wasn’t anyone around that I could speak with so I was not able to get more information about how this decision was made or how it worked for their community.

St. Gregory incorporates movement into their liturgy and the architecture makes that possible. The early service starts with participants sitting in the bema area but the later service starts around the altar (see previous blog post about later service) and the participants move to the seating area after the initial greeting, blessing, and song. After the liturgy of the word, both the services participants move from the bema area to the altar for the Eucharist prayer and communion they hold onto each other’s shoulders with one hand while dancing a simple step right, step left, step back, step together, and repeat. When at the altar, the gathered community continues to move around circling the altar until everyone is present. At the end of the service a chorus (song with dance) is sung and danced with a simple grapevine step around the altar.

In a document that Richard Fabian, co-founder of St. Gregory, wrote he describes the thoughtful process of the architecture formation of St. Gregory’s in this way:

As we advocate for shaping liturgical practice so people can make affective theological discoveries from one another’s faces, breathing and movement, practice and theology, we should pause to acknowledge the questions of conservative liturgical writers who ask of us where we expect people will direct their attention during the liturgy and what kind of attention we’re hoping to teach them to offer each other. The liturgy we could offer our architect when we asked him to design us a new church was a genuinely new ceremony.

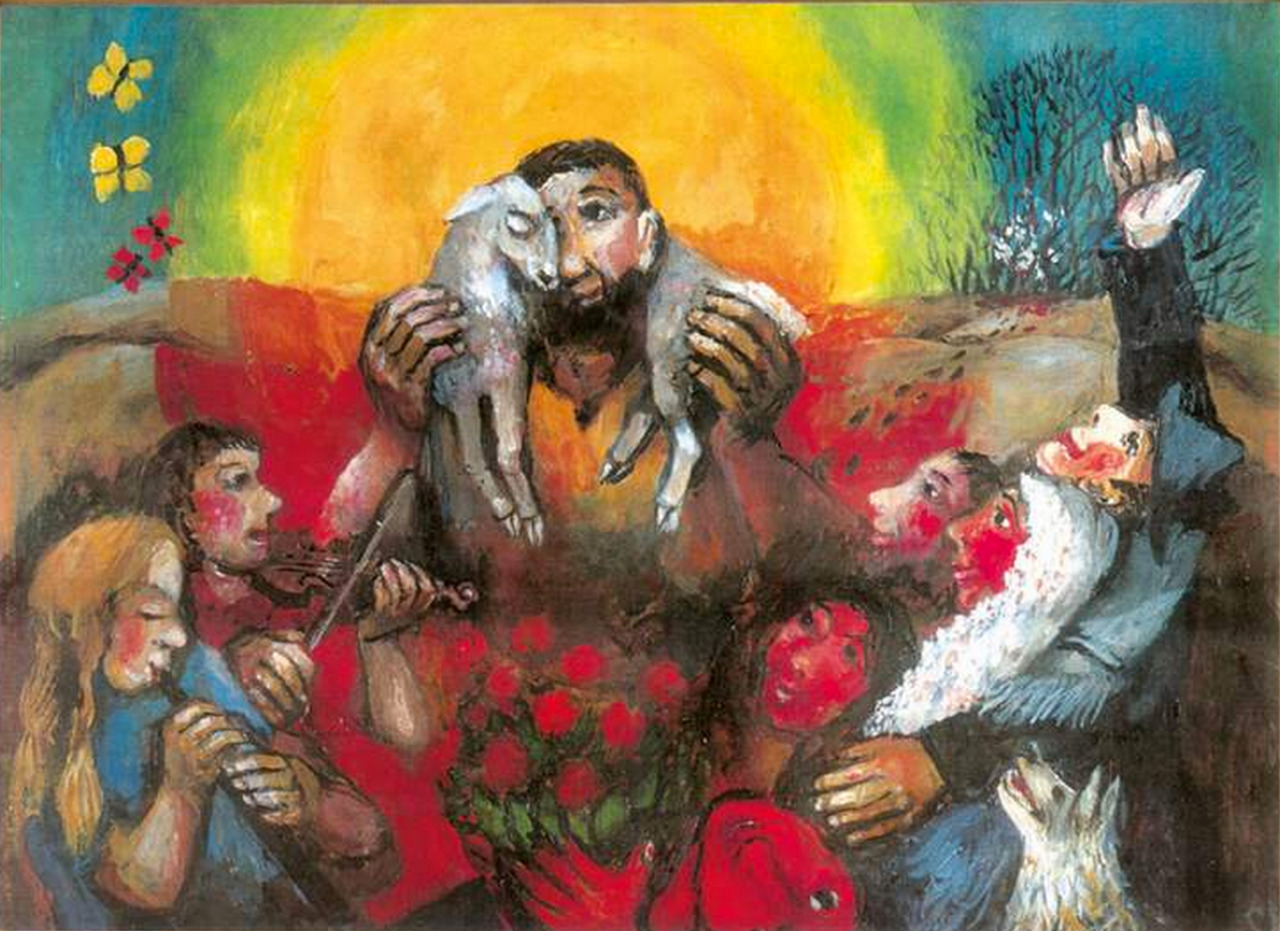

The words that both Rick and Donald, co-founders, use to describe this “new ceremony” are “context of affection.” Context of affection can be applied to both the architecture and the liturgy. The architecture, with its natural light, its open feel, its beautiful art, and its focus on the altar, invites one to enter the building and to interact with one another and with the space. When I entered St. Gregory’s the first thing I noticed was the altar sitting alone in the middle of the rotunda. It seemed both majestic and lonely all at the same time and invited me to draw near and touch it but with reverent hands and a humble heart. Shortly after people arrive and gather around the altar the liturgical leaders walk among the people and greet and shake everyone’s hand—the fact that we are all standing in an open space makes this possible. The liturgy with its movement and dancing are also possible in this open space, which invites the fidgeting of children, the rolling of wheelchairs into positions of inclusion, and adults that do work by singing, reading, and moving to the rhythm of the liturgy.

Rick describes the process this way:

Journeying through the liturgy in a dynamically structured sacred space formed our congregation for collaborative leadership, participation of the whole company, giving

ordained and lay leaders genuine authority to lead, and congregants invitation and authority to act and the means to act together.

I started with the question: What does our architecture say about the way we worship and practice corporate liturgy? And end with acknowledging affirmatively that St. Gregory’s architecture and liturgy are intertwined in a way it is hard to see where one ends and the other begins. So, yes, our architecture says volumes about our liturgy and vice a versa, and this is something I’ve learned that I need to consider as I contemplate liturgy and context. More to digest…